Governance Era

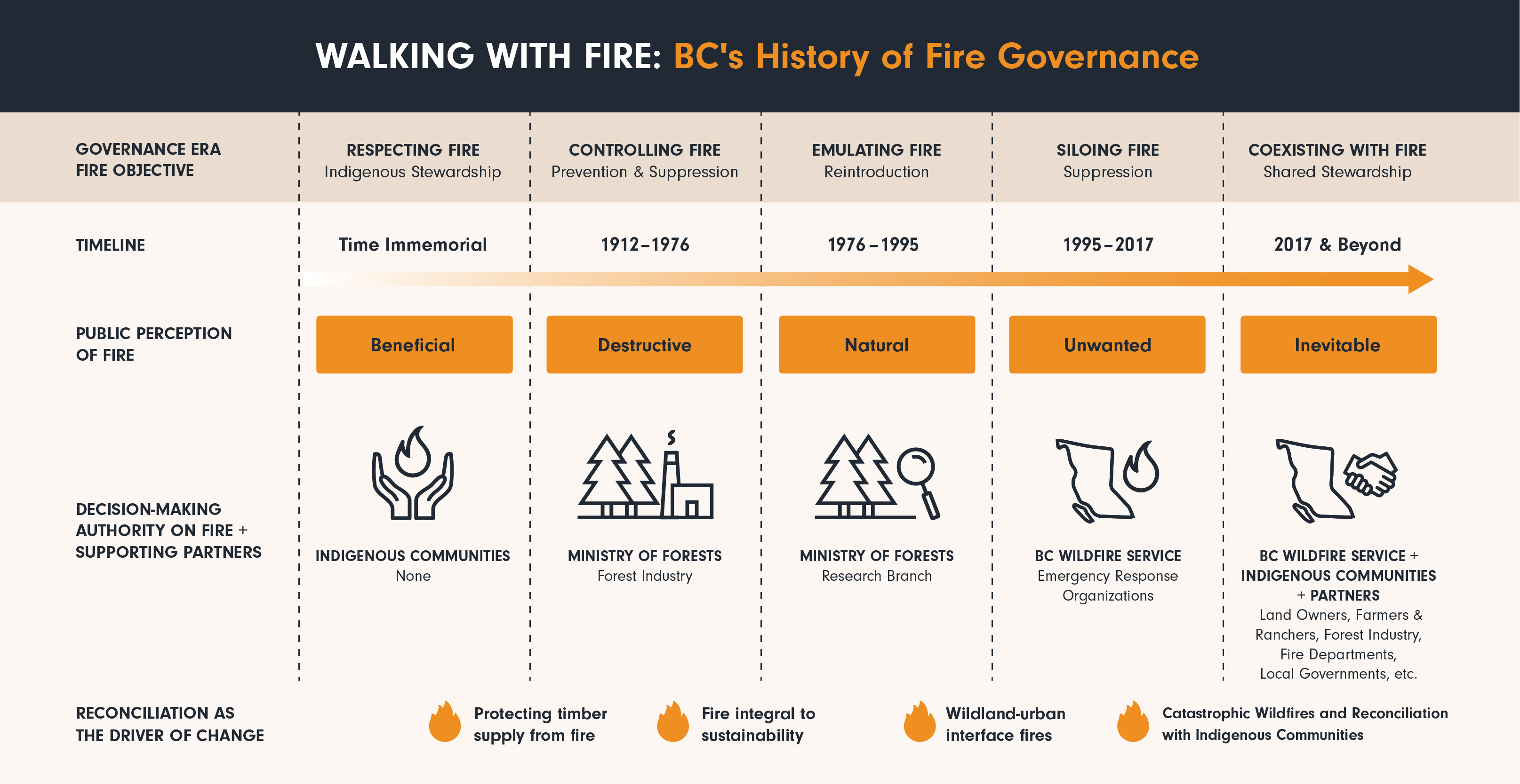

Governance, as it is used here, is defined as attributes that influence environmental outcomes, including organizations or individual actors, objectives, legislation, decision-making power, and worldviews. Eras are defined based on periods when governance attributes remained relatively consistent and shifts in eras are demarcated by key drivers of change.

Respecting Fire

Since time immemorial, First Nations stewarded fire under their own systems of governance for a variety of cultural, spiritual, and ecological objectives. These systems of governance reflected a worldview of fire as beneficial for biodiversity and cultural continuity, although experiences with fire varied and burning practices were not universal.

For some First Nations, fire stewardship is a year-round activity that involves different activities during different seasons, including times to mitigate, times to burn, and times to harvest fire-affected landscapes. Fire stewardship includes, but is not limited to, cultural burning, interacting with lightning-ignited landscape fires, and respect and care for the broader land base in ways that beneficially affected fires’ impacts.

In contrast to early settlers, federal and provincial government actors sought progress by denying the benefits of First Nations’ fire stewardship. The Bush Fire Act of 1874, for example, which focused on fire prevention objectives through strategies such as financial penalties for setting fire and prohibiting burning except by permit, began to institutionalize the colonial worldview of fire as destructive to timber.

The transition away from First Nations governance was reinforced by the establishment of Indian Reserves and Residential Schools by the federal Indian Act, pre-emption policies restricting First Nations’ access to land, and the smallpox epidemic that killed up to two-thirds of First Nations peoples in BC.

Indigenous stewardship includes a range of cultural and land management practices, including language transmission, learning from the land, intergenerational knowledge transfer, and management activities like cultural burning.

Cultural burning has existed since time immemorial, with traditional knowledge passed down from generation to generation. It holds different meanings for different Indigenous communities but is often defined as an Indigenous-led practice of intentionally applying fire to achieve cultural, spiritual, and ecological objectives.

Controlling Fire

This era cemented centralized colonial fire governance through the creation of the Ministry of Forests by the Forest Act in 1912. The Forest Act enshrined the worldview of fire as a “common enemy” of timber industry actors who were the “commercial backbone” of BC.

The Forest Act legally mandated the Ministry of Forests, which directly managed the BC Wildfire Service, to control fire on provincial Crown land. The Forest Act also gave the Ministry of Forests authority to enforce fire prevention strategies such as financial penalties and jail for people who “wilfully set fire” without a burn permit or refused to provide firefighting assistance.

These strategies disproportionately affected First Nations, who attempted to continue their fire stewardship practices but were often forced to uphold colonial worldviews and objectives.

Colonial practices focused on strategies such as financial penalties for setting fire and prohibiting burning except by permit, and even jail for people who “wilfully set fire” without a burn permit or refused to provide firefighting assistance.

Reintroducing Fire

Although the Ministry of Forests continued to promote the worldview of fire as destructive, improved fire ecology research prompted the emergence of the worldview of fire as natural in the early 1970s. In 1976, the Royal Commission on Forest Resources acknowledged that “controlling fire and other natural forces” was permanently changing ecosystems in BC.

Reflecting this worldview shift, a new objective of reintroducing fire was added. Prescribed fires became a key strategy for ecosystem benefits and fuel reduction. The Ministry of Forests also worked closely with other actors to reintroduce fire, including the “forest, ranching and wildlife industries…and the Ministry of Environment,” who retained authority over wildlife and parks.

The BC Wildfire Service continued to focus on its fire control objective, self-identifying as a “world leader in fire control and suppression.” Nevertheless, expertise on fire and forest management was connected because of the close integration of the Ministry of Forests and BC Wildfire Service.

Revitalizing cultural fire as a primary objective provides an opportunity for First Nations peoples to reassert their knowledge by holding decision-making authority. This authority is key for transformation because fire-related objectives are intimately playing out on Indigenous peoples’ unceded traditional territories, and they have their own expertise of fire.

First Nations-led or co-governance models could share decision-making among actors. Redistributing decision-making authority recognizes that the current command and control model is often inequitable.

Major events, motivations or circumstances that have changes the fire governance approach in B.C. These include environmental or economic factors, public safety and socio-political changes.

Siloing Fire

In this era, the BC Wildfire Service became a stand-alone organization in 1995 under the Ministry of Forests, creating organizational silos and uncertainty over roles and responsibilities, especially as other emergency response organizations became involved. Notably, when the BC Wildfire Service became a stand-alone organization, it was under the Protection arm of the Ministry of Forests, signalling the continued commitment to timber values first and foremost.

The “2003 Firestorm” was a catastrophic fire season that forced evacuation of over 45,000 people and demonstrated that relying on fire control alone was inadequate for public safety. A subsequent independent provincial review into the causes and consequences of the 2003 Firestorm acknowledged that the “success” of fire control since 1912 contributed to the widespread negative impacts.

First Nations and local communities who were exposed to Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) fires emerged as key actors in this era. The Union of BC Municipalities and the newly formed First Nations’ Emergency Services Society (FNESS) administered new funding to support communities.

After the 2003 Firestorm, new legislation helped actors understand their roles and responsibilities undertaking multiple fire objectives. The Wildfire Act and Regulations (2004) aimed to improve accountability and clarify liability, especially for forest industry actors, and the BC Wildfire Service underwent a “strategic shift” to prioritize proactive objectives and overcome silos.

In western North America historical and ongoing policies of fire suppression have resulted in a build-up of hazardous fuels, an increased fire risk, and decreased forest resilience. Furthermore, historical suppression policies interrupted Indigenous fire stewardship that historically maintained biodiversity.

Coexisting With Fire

This era is dynamically emerging in BC in response to catastrophic fire seasons since 2017 and efforts towards reconciliation. The inevitability of fire became clear during the 2021 fire season, when two lives were lost after nearly 90% of the community of Lytton was destroyed.

These ongoing tragedies have prompted an emerging vision for coexisting with fire that is a focal point for potential transformative change in fire governance where community actors have more involvement and contributions to decision-making. Community involvement is crucial not only because it helps develop the “social licence” needed to enable proactive objectives but also because it helps to recognize that “expertise is everywhere.”

Collaborating with First Nations communities as partners and leaders is a central component of the evolving vision for coexisting with fire, especially given BC’s legal commitment to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The First Nations-led revitalization of cultural burning and land stewardship is a crucial pathway for increased decision-making authority. Both the BC Wildfire Service and Ministry of Forests are committed to prioritizing proactive objectives, including cultural and prescribed fire.

Shared Stewardship is a collaborative approach to land management that focuses on partners working together to establish joint priorities and opportunities. It encourages development of objectives and strategies across jurisdictions at a larger scale. Through Shared Stewardship, partners are coming together to address these challenges and explore opportunities to improve forest and community health and resiliency so that we can all continue to coexist with fire.